|

|

||

© Open a High-Resolution, Half-Screen Version in a New Window |

|

§ Open a High-Resolution, Full-Size Version in a New Window |

|

||

© Open a High-Resolution, Half-Screen Version in a New Window |

|

§ Open a High-Resolution, Full-Size Version in a New Window |

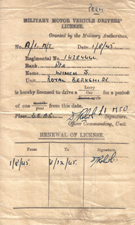

Although John didn't shy away from talking about the Far East, it was only in his later years that he wrote of his experiences in detail. This is John's own story. I was sixteen when war was declared in 1939, learning my trade as a woodworker. In September 1942 I was called up for National Service. I asked to be allowed to join the RAF but the order had obviously gone out for infantry and I had to report to Colchester for basic training. After six weeks basic training, a week's leave and six weeks specialist training, I arrived in Norfolk for intensive infantry training. Then two weeks leave, back to Norfolk to prepare and wait for the time when we would have to leave for service abroad. We embarked at Greenock on a converted Dutch Cargo Ship, the Schlokradite. The holds had been fitted with bunks, five high. I managed to pick a nice one on the top. We were given two meals a day, served at a cafeteria into segmented trays by the American crew. We stood and had to save some of our breakfast for a snack lunch. Most of us were given daily tasks. I was told to report to the ship's carpenter to help him, but found that someone else had already been given the job, so I was reallocated to potato peeling. This turned to my advantage because, being connected to the galley, I was given food at lunch time and was off duty all afternoon, whereas the ship's carpenter worked until 5:30pm. The first few days at sea were bad everyone except the crew suffered from the motion of the boat. Then one day the crew brought some barrels of apples on deck and told us to help ourselves. The apples seemed to settle our stomachs and we slowly recovered. We stopped at Freetown to take on fresh water but were not allowed off the boat. We then went on to Durban where we stayed for five weeks, then sailed on the Strathaird to Bombay. After landing we travelled by train to Deolali near Poona then, after a couple of weeks, on to Ahmadnagar where we joined our regiment, the 1st Battalion Royal Berkshires. Everything here had to be done by the book. Spit and polish was the order of the day and a very hard session of training began. I had an attack of dysentery and spent a week in hospital. Shortly after, we travelled to southern India to carry out special jungle training. Then we were rushed back to barracks to prepare for action, and left a few days later for Assam. Having had training as a driver, I was transferred to the MT section as a co-driver, and we formed a 250 vehicle convoy to take all our equipment. The Journey took 3 weeks, a story in itself which I will try to tell later. |

||

© Open a High-Resolution, Half-Screen Version in a New Window |

|

§ Open a High-Resolution, Full-Size Version in a New Window |

We arrived at Dimapore to learn that the Battalion had travelled by train and had been in action for a week by that time. The following day I was detailed to take some supplies to a point just a few hundred yards from where our company was dug in (someone else would take the supplies up to them under cover of darkness). The following night all the co-drivers set off to join the company, led by a new young 2nd Lieutenant. I was expecting to turn off the road at the place where we had left the supplies the previous day, but we passed that spot and continued along the winding road with hills towering above us. Then someone challenged us and almost immediately grenades began to explode around us. Someone answered the challenge by shouting the password and we turned back, arriving at our starting point. So the whole thing was called off. We set off again the following morning and had to join the company under fire from the Japs who were positioned just a short distance from where we had been on the previous night. The company were dug in on the hill over looking the tennis court of the District Commissioner's bungalow where they had taken over when they relieved The Royal West Kents. There were a lot of trees around, most of which had lost branches and leaves from enemy gun fire. There were parachutes dangling from the branches with supplies still attached, but out of reach. Dead Japs were strewn all over the area and the stench was very strong, and remained with us for a long time. Even weeks after leaving, the memory of the stench would return. The first news that we received was that due to heavy casualties there were only 5 men in a section, therefore guard duties were increased. We were under constant threat of enemy fire during daylight, so contact with other sections was very dodgy. Water was rationed, and we were not able to wash or shave. Rations came from the air drops, and were mostly tinned food and dry biscuits. We managed to stop the Japs making any counter attacks, but not without more casualties. This went on for a few weeks during which we lost all idea of time or dates. Then one day someone had worked out the date and I realised that it was the day after my 21st birthday! One day we came under enemy artillery fire. My best mate Les, who had been with me since the day we joined the army, was killed. This was a shock. I suppose that I was lucky not to have been hit. A few days later our platoon set off into the hills to try to find the Jap artillery. By this time the monsoon had started so our progress was slow. We had to climb up into the heavily wooded hills and were soon drenched by the very heavy rain. The first night was spent standing up under the trees trying to dodge the rain, but come the morning we were soaked and tired and utterly miserable. That day we came to the place where we had expected to find the Japs. There was grass growing to about 18 inches high and hidden in the grass were bamboo stakes set into the ground at an angle, with sharply pointed tips facing us. We were lucky to spot them before anyone had walked into them. The Japs had left, but must have spotted us and then attacked us the following day. They left as soon as we returned their fire. At this time all our drinking water came from pools and puddles wherever we could collect it. We carried sterilising tablets but these did not improve the flavour. After leaving one camp area we discovered that the water which was running into a pool which had been used to fill our water bottles, was flowing over a dead mule. Happy days! The search for the Jap artillery was given up, and we had a few days to relax. At this time someone decided that we could do with a bath - they must have been standing down wind of us! A couple of three ton lorries turned up and off loaded 40 gallon petrol drums. These were split down one side and across the top and bottom, then folded open to form a pair of baths. Water was heated by the cooks on their petrol fired stoves and we stripped off and sat two by two facing each other, and enjoyed the best bath of our lives. When we removed our boots and socks, our feet were purple from the dye in our boots and were all wrinkled through having been wet for such a long time. There were also a lot of leeches attached. These had to be burned off to prevent pulling the skin off. We were given new clothes and boots before moving on. By this time the Japs had fled from Kohima. Other units in the Brigade were pushing along the road towards Imphal to relieve the men who had been trapped there for several months. Someone in their wisdom decided that we should have a rest, so we set up camp just off the Kohima to Imphal road. At last we were under canvas and could keep dry, at least at night. We started to get a few perks like the NAAFI and an occasional mobile cinema. It was here that I had another attack of dysentery. After a few weeks of relaxation we set off into Burma. Imphal had been relieved and The African Brigade had taken over the lead in a push to keep the Japs on the run. They then crossed the Chindwin and formed a bridgehead. It was here that we took over the push. We kept close to the main road to start with, coming under occasional fire from small pockets of Japs. Our progress was delayed by trees which had been felled across the road, with a few booby traps throw in. Eventually our platoon was sent into the country, away from the road, to get behind the Japs before they could fell the trees. It was Christmas Day 1944 when we set off, and had not left the road when we were strafed by a Jap Zero fighter plane. One man was killed. Most of us managed to shelter behind the big trees at the edge of the jungle. It was not a nice experience. We proceeded to get behind the Japs but came under frequent fire. In fact this was the only way that we could locate them. They were expert at hiding and very hard to flush out. We were fortunate when we could direct our artillery onto them. Even so they were often in bunkers, with tree trunks over their trenches, and well concealed by bushes etc., so that they were unaffected by the artillery shells. We then had to go in and flush them out, not without risk of casualties. We carried on in this way for a couple of weeks, then one day a message was passed back saying that some Japs were waving to us, so a section was sent forward to find out more. It turned out that the wavers were in fact Gurkhas, and we were invited to join them for the night. The Gurkhas were on a deep penetration patrol, and had formed a perimeter for the night, so we joined them. We were not allowed to form a guard that night. This had already been arranged and we were given the night off. The Gurkhas were delighted to have us with them. They produced rations for us, from a supply of English food which had been dropped to them by mistake a few days earlier. They sent out a patrol just as it was getting dark and it returned the following morning. The men were all smiles because they had met up with some Japs during the night. We had not heard any firing and the Gurkhas were carefully cleaning their Kukris, so we assumed that they had sorted them out in their own way. We parted shortly after, each going our own way. We were sorry to leave them and were very pleased to have met them. A few days later my section was detailed to carry out a forward reconnaissance, with a Captain leading us. We were to determine whether the road was clear at a certain bend. We were already camped a few miles from the road, so stayed hidden until we reached a spot about a hundred yards before the bend. The Captain and our Sergeant then went on ahead. Shortly afterwards a shot rang out, then the sergeant returned to say that the Captain had been killed by a sniper as he reached the road. We radioed back to base, and were told to return. The next day we went to the same spot where we laid low while the artillery laid down a very heavy bombardment of the area where the sniper had fired from. We then went in to sort out anyone who might have survived. We found the bunker where the Japs had been, and a few Japs who had been hit by the artillery. We then started to check the area around ,and were fired on by a sniper. Two of our men were hit by the sniper. I and a few more were pinned down. I tried to crawl towards a bush and two or three bullets hit the ground around me, so I decided to play dead. After ten to twenty minutes, I took a chance and made a quick dash to get behind a tree, and was lucky, I tried to see if the Jap sniper could be located, but could not determine where he was. At this point I realised that when the bullets hit the ground around me, I didn't hear the shots. I had been told previously that you do not here the shot that hits you, so I must have had a few close shaves! After a few minutes behind the tree, I decided to try to rejoin the rest of the platoon who were concealed from the Jap higher up a slope, so I made a quick dash towards them. They immediately started to cheer me on and I managed to reach them before the Jap spotted me. A few minutes later the other men also made a dash up the slope. Unfortunately one man was hit. We tried to get around the sniper and another man was hit. At this time my ankle gave way when I caught my foot in a hollow, and the MO strapped me up and sent me back to our rear echelon by an armoured ambulance. I spent about a week behind the lines before they allowed me to rejoin the platoon. Then we were told that we were to start a new tactic. The Brigadier sent a message to thank us for our recent efforts. He now wanted us to push forward at a much faster rate, We were to travel light and at night, using tracks, not the road. Local guides would help us to make a fast advance. Resting during the day ,and travelling only at night, we made very good time advancing 25 to 30 miles a night for about a week, without seeing any Japs. One morning we stopped by a wide but fast flowing river, and were able to have a dip. One of our section found a cache of Jap hand grenades. We organised a line of us across the river while grenades were thrown into a deeper pool. This stunned the fish which floated on the surface towards us, and we were able to throw them out onto the bank. We enjoyed these as a nice addition to the quarter rations which we had survived on for many weeks. We had two hard biscuits each with our fish for breakfast. On another occasion we met up with some Japs and had to dig in to form a defence. This was on the edge of a banana plantation and we cut down some of the bananas at ground level to give us a better view. We stayed here for five days by which time the bananas had grown to about three feet high again. We were then able to push ahead at a good pace again without meeting many Japs. We joined up with the other units at Meiktila and were flown out to a camp near Calcutta. We were given special rations, with lots of fresh fruit, meat and other treats. Then started training with the Royal Navy for a seaborne landing. We went out every day on ships which were fitted out for landing craft and practised scrambling up and down nets into or out of landing craft. Then we made landings on local beaches, getting very wet at times, each day returning to our camp for the night. Then some men fell ill with a stomach bug and each day more men went down. I had just begun to think that I had escaped when I caught it. Unfortunately I also had a return bout of dysentery and was taken into hospital. By the time that I had recovered, the Battalion had left for the landing into Rangoon, They met no resistance and I was able to rejoin them a few days later. We were kept in limbo for a short period while the powers that be made up their minds what to do. Eventually we were sent into the Irrawaddy delta area where some dacoits had been raiding local villages. The Royal Navy provided the transport and we camped wherever we could find some shelter. We never caught up with the bandits. They had always left just before we arrived. Did they have some inside information, or were they just a figment of someone's imagination? It was while we were there that we heard about the dropping of the Atom bombs on Japan. We were allowed a few days rest to celebrate the end of the War, then we moved back into the Rangoon area and made camp in empty houses on the outskirts of the town. We were not allowed to relax very much. Someone found a number of places that required overnight guarding so every night we had to mount guard on these buildings. We never did find out why they needed to be guarded. |

||

© Open a High-Resolution, Half-Screen Version in a New Window |

|

§ Open a High-Resolution, Full-Size Version in a New Window |

The time came when the Battalion was to go home. Only men who had travelled out with the Battalion were allowed to travel home with it. The remainder, which included me, were transferred to the 2nd Battalion. We had a long journey up to the north of Burma where the 2nd. Battalion had been sent, because someone was worried about the Chinese who were in occupation just north of the border. There was not much to do. The air was much cooler and we were camped in pine covered hills. One day a notice was fixed to the board outside of the Company Office inviting anyone who had worked in the building industry to attend a refresher course in their particular trade. I put my name down and a week or so later I was told to pack my kit. I was to go to Rangoon the following day to join the course. So there I was on a truck, just the driver and myself on the long drive back to Rangoon. I had been attending the course for a few days when the Instructor said to me that I had obviously had some experience in the trade, which the other men equally obviously had not. I told him of my work prior to joining the army. The Instructor asked me if I would be prepared to go to an Indian Army camp to assist in teaching Indian service men in the basics of building. I agreed, subject to getting approval from my Battalion C.O. The approval came through very quickly and I was taken to the Indian camp about 30 miles out of Rangoon. A Sergeant was there also, and he told me that the object was to show the Indians how to construct a dwelling using the natural materials which they had to hand. So we started by making a timber framed building, using small trees of approximately 4 inches diameter, with the branches cut off flush but with the bark still attached. These were collected from the local timber yard. The timbers were jointed and lashed together with strips of a special tree bark which the locals brought to the site. The lashing had to be done while the strips of bark were still green. They then tightened up as they dried out. The roof was thatched with palm leaves which again were lashed to the timbers, working from the eaves to the ridge with approximately half a leaf overlap. They made a good watertight cover. This was the basic work, which demonstrated use of wood to form the sides and the formation of door and window openings, the method of supporting the roof using purlins and rafters, and the use of principals to support wider spans. The walls could then be filled in using their traditional methods, which was usually mud and cow dung! It was a good experience to live so closely to the Indians, and although we did not understand each other very much we were able to learn a lot about their way of life. They treated us to dinner, producing the hottest curry that I have ever tasted. It is a custom that the hotter the curry the greater the tribute to your guest. So we were greatly honoured! The Indian camp had a film show every night, in the open. They all squatted on the ground - we preferred a seat - but the films were mostly Indian comedies and quite enjoyable. There was a Mango tree at the side of our billet and the season was right. We were able to pick the mangos green, then set them out on a ledge in the sun to ripen. When they had turned to a bright orange colour we ate them, usually with the sweet sticky juice running down our chins. I have never tasted anything like it since. I returned to Rangoon to find that the building course was finished. My Battalion had decided that I was to stay in Rangoon to await my repatriation, so I had a cushy time for a few weeks, only having to attend roll call each day. I had met up with a mate who had also been doing special duties in Rangoon so we kept each other company. The troop ship duly arrived and we set sail for home. My mate was a very bad sailor and was not able to go below decks for fear of being sick. I felt a bit that way but was able to go down for food etc. I went below to the mess deck to eat and made my mate's food into sandwiches for him to eat on deck, and we were nearly through the Indian Ocean before he could be persuaded to go below. Most of us slept on deck at the start of the voyage, because it was so hot and stuffy below. We stopped at Colombo, but were not able to go ashore. We then began the journey through the Indian Ocean, stopping off Aden, then through the Red Sea and the Suez Canal to Port Said, then through the Med to Gibraltar, along the Spanish and Portuguese coasts to the Bay of Biscay, then into the Channel and on to Tilbury - three years and eleven months after leaving Greenock. My story does not finish here I had to remain in the army until my turn arrived to be demobbed. I was given a medical examination and was passed A1. Then they gave me a suit and a few other items of clothing, my back pay, and a travel warrant to get me home. I took a few weeks off before starting to work again as a wood worker. In the mid 1950 period I began to suffer with stomach pains and was given antacid medicines by my doctor. He told me to stop being a worry guts. This went on in varying degrees until 1967 when, after a bad bout of pain, I was sent to see a specialist who diagnosed a gall bladder problem. So after some painful weeks of waiting I was admitted to hospital to have my gall bladder removed. Then they started the operation and found a large abscess in my liver. So began a long stay in hospital while they tried to discover what had caused the abscess. After 3 months in the local hospital I was transferred to The Royal Free Hospital in London to be under the care of the leading liver specialist of that time. Three months later they operated again and were able to prove what had previously been suspected, that the abscess was caused by an amoeba which had remained dormant in my liver since the last attack of dysentery while I was in Burma. The operation left me with a massive clinical hernia causing me to require a surgical belt. I was eventually allowed home after 7 months in hospital, and able to return to work after 10 months away. J. W. In April 1960 John married Margaret Duckworth |

||

© Open a High-Resolution, Half-Screen Version in a New Window |

|

§ Open a High-Resolution, Full-Size Version in a New Window |

|

||

© Open a High-Resolution, Half-Screen Version in a New Window |

|

§ Open a High-Resolution, Full-Size Version in a New Window |

|

||

© Open a High-Resolution, Half-Screen Version in a New Window |

|

§ Open a High-Resolution, Full-Size Version in a New Window |

|

||

|

||